Sabine Giron

Tell us a bit about your background.

I’ve been interested in everything to do with robotics since high school, so I went down that route into further education and got a Master of Engineering from IMT in Lille. It was a general engineering program, however I specialized heavily in automation. I then achieved a Master of Science at Cranfield where I focused on unmanned vehicles and my thesis was on reusable space planes. After graduation I joined the robotics group at Irish Manufacturing Research as a research engineer. We started as a very small team with limited equipment and grew up from there into a diverse group with many capabilities in terms of skills and technologies, building a large lab with pilot lines and robotics cells. We ran projects looking at the risks and challenges that manufacturing companies face in Ireland. My involvement covered robotics, vision systems and innovation systems so when the opportunity to become IMR’s LER on the DIH² project arose, I thought it was a great opportunity for me to use my enthusiasm for something that would be really impactful.

The field of robotics has been dominated by men up until now. Why do you think that is and what can be done to change the gender imbalance?

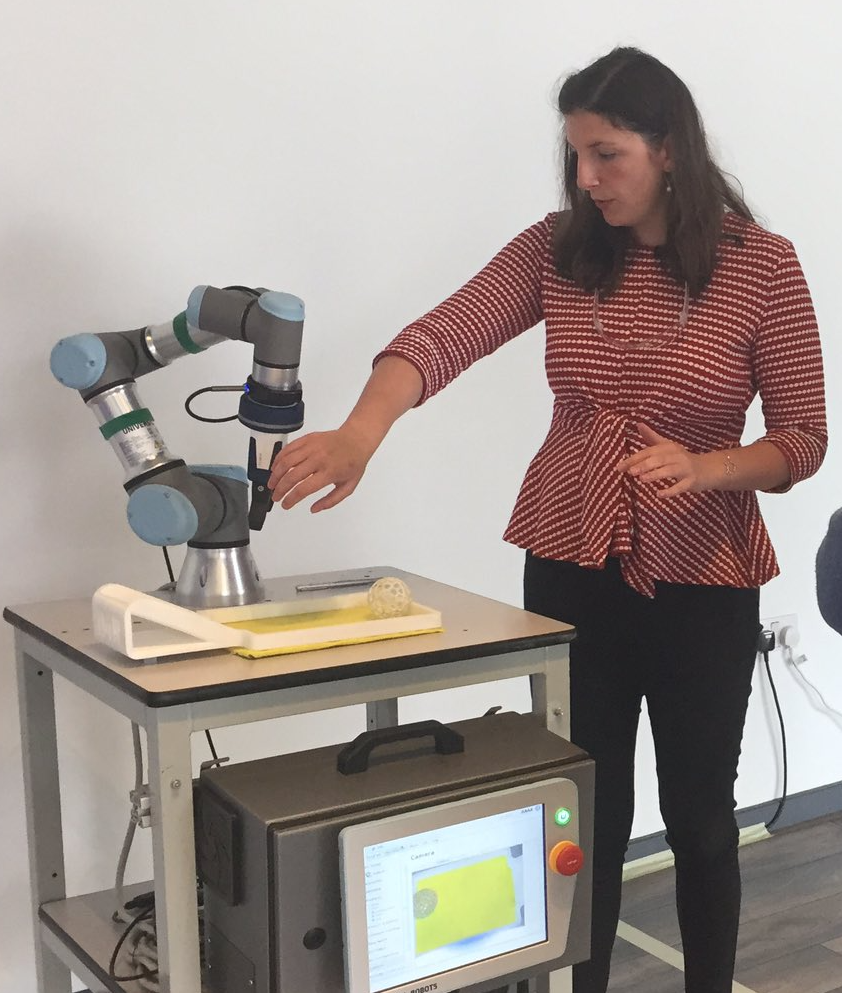

This has fundamentally been an issue of unequal opportunities. Historically engineering and robotics wasn’t something that was pushed in front of girls in secondary education and even today there are few female role models to drive the ambition of young girls. During my university studies I was often one of only 2 or 3 women in the class. At IMR, we had 3 women in a department of 10, so still an imbalance but IMR was very keen to drive gender equality. We developed an outreach program to improve access to opportunities for girls. Through that, we brought high-school classes to IMR where we would firstly ask the girls what they wanted to be when they grew up, and secondly, we’d ask them to draw a picture of an engineer. The girls would often say that they wanted to become veterinary surgeons or architects – fine professions obviously - but very rarely did they want to become engineers. And when they drew an engineer, it would inevitably depict a man with a tool and a helmet. We’d then run workshops where we’d introduce them to robots. For the younger ones, we’d make the robots dance and play games, and with the older girls we’d teach them how to conduct some basic programming of the robot. The level of satisfaction they’d get from this was amazing. It was incredibly rewarding to see the sparkles in the girls’ eyes. Some of them would tell me that it was something they had never imagined they could do – that robotics was somehow not for girls, not for them. To be able to open up the spectrum of potential is so important. Even if they choose not to go into robotics, they now know it’s out there and it might also open their minds and curiosity to other fields. We’re able to show them what’s possible by connecting a concept to an idea and seeing a woman working in that field makes it real and tangible for them.

What female role models did you have when you were in high school?

None specifically in robotics, but I was inspired by all the women in science – the ones that were the first to do what they did and showed what could be possible. Marie Curie, obviously. But then also someone like Maya Angelou who opened-up and changed society. For me it wasn’t one woman, rather a combination of all the women who made change happen.

The DIH² Network is about agile production in manufacturing. From your experience, what sort of challenges do you think SMEs are facing when it comes to agile production?

In my time at IMR what I’ve seen when visiting manufacturing SMEs is that they are focused on day-today challenges. When they want to introduce new technology there is an associated risk. A lot of them lack the technical resources, human resources, and financial resources to fully evaluate and de-risk so they often choose not to adopt new technology. Agile manufacturing means not sticking with the status-quo and the status-quo means you won’t be able to adapt to market changes as fast as is needed, especially when it comes to digitization. It’s not necessarily a reluctance to introduce the technology - they have the vision and often even a roadmap, but they lack the time and resources. This is where programs such as DIH² come in – we have the resources, the funding, and we can connect them to people that can help them with these challenges.

One of the key goals of DIH² was to fund Transfer Technology Experiments in agile production. Your project was STAR (Stitching and Taping Assisted by Robotics) in Ireland. Can you tell us a little about it?

STAR was composed of an end-user SME called Ventac, based just to the southwest of Dublin, that specializes in the design and manufacture of noise control solutions used mostly in commercial vehicles and large-scale industrial facilities, and the technology partner was Malone Group, headquartered in Dublin, who help design, manage, and deliver high-value business-critical projects. Ventac’s production is highly flexible which allows them to run small batch sizes - often fewer than 20. Their challenge was to maintain that flexibility and scale it to meet customer demand. There was a lot of work-in-progress using factory space and this inevitably also meant that money was tied-up in WIP. The manufacturing of acoustic panels requires stitching to put them together and to date this has required a highly skilled workforce. In common with many other parts of Europe, there is a shortage of skilled workers that can do what they need so it was very challenging for them to increase volume and productivity and this in turn was limiting their ability to expand. STAR project was about creating a step-change in the digitization and automation of processes within the Ventac facility including a partial automation of the stitching and taping process. The project used a demonstrator robotic arm to guide panels into stitching machines as a human would have done. The initial aim was to automate the stitching of at least 10 different models of panels and to then build out the solution to create an expanded library for the production process.

What did it take for you to bring STAR together?

We organized a match-making event that was attended by more than 20 participants - both tech providers and end-users - where we provided an overview of the DIH² project. Then each of the end-users presented their specific challenges and the technology providers presented the services and support that they could provide. After that we facilitated one-to-one discussions and Malone and Ventac began their relationship from there. I then continued to work closely with them through the proposal stage and to the pitch to the DIH² jury where happily we were accepted into the project.

What complications did STAR have to overcome?

This type of experiment always throws up challenges. In our case, the first was digitization. Malone was highly experienced in automation and robotics but needed to learn new technology, such as the Grafana dashboards, quickly. We received a lot of help from experts and the wider DIH² Network here, especially when it came to FiWare and developing a ROSE-AP. Separately, STAR involved delivering an industrial proof of concept. i.e., the reality of the product’s viability. We started with a robot conducting tests at Malone and then progressed to installing a demonstrator in Ventac so that we could test and refine the solution within the industrial environment.

What does the future look like for STAR?

The goal of experiment was to investigate what was possible and this has been a success. Ventac now has a roadmap to automation - they estimate that STAR could automate up to 15% of their production by using robots and humans together in a collaborative way to drive overall efficiency. Meanwhile, Malone has built invaluable experience that will enable them to launch further projects.

Our network has a diverse and wide-ranging membership - both in geographic terms and the sectors that the partners operate in. What were your experiences of working in such a diversified structure?

Having the diversity is so important. We all come from different backgrounds, different countries and have varying approaches. Within DIH² there is always someone who will challenge the status-quo, someone trying to improve a solution or an idea. Discussion is going on constantly – there are lots of exchanges happening - knowledge, know-how, best practices and so on. For example, I might be struggling to find a solution to something and then I discover that someone else has already done it, so I don’t need to reinvent the wheel. You clearly see the power of the network on these occasions. On a more light-hearted note, I also learned a lot about the history of all the various bank holidays across Europe!

What would you say to an organisation that is considering joining the network?

Obviously, do it! We all have a responsibility to contribute to European robotics. Rather that defending self-interests, we all need to cooperate more. Being in the DIH² Network allows us all to access the knowledge that already exists, the best practices that already exist, and for us all to learn from each other.